Working Paper

How Recife responded to the challenge of learning deficit...

May 12th 2025

School closures during COVID-19 caused learning losses worldwide, often compoundin...

Read More“You’re telling us that we’ll have to sell products in the village to earn extra income,” began one woman during our interaction with a Cluster Level Federation in Budni, Madhya Pradesh (MP), “But what about all the people who’ll make fun of us?” This took us by surprise. Until that moment, despite all our planning and knowing fully well that the women would have questions and concerns about the proposed social enterprise model, this wasn’t something we had imagined as a significant potential barrier to their participation. The days that preceded and have followed since have elicited many such moments that became profound lessons for us during this initial phase of our work in rural MP.

This meeting was one of the many interactions we had in working to introduce an innovative agro-processing model into women’s collective enterprises in rural India. The model aims to integrate an agriculture value chain in ways that provide opportunities for additional income generation to rural women. It involves village women procuring from local farmers, processing products in a collective enterprise, and then house-to-house selling. The inspiration for this model comes from RUDI, an innovative social enterprise pioneered by Self-employed Women’s Association (SEWA). SEWA is a union of self-employed women founded in 1972, based on the Gandhian principles of simplicity, self-reliance, and strengthening of women’s leadership. RUDI was formed in 2004 and has successfully grown within Gujarat as a financially sustainable social enterprise.

IMAGO and SEWA are now adapting and scaling the RUDI model through one of the flagship programs of the Ministry of Rural Development in India—the National Rural Livelihood Mission. This program aims to organize poor women into self-help groups (SHGs) to enhance economic empowerment, and has an enormous reach throughout rural India, so provides an opportunity for genuine scaling.

We are currently implementing a pilot project in the Budni block of the Sehore district, supported by the MP State Rural Livelihoods Mission (SRLM) and SEWA. As part of the pilot, we are establishing an agro-processing enterprise that will be owned and operated by a Cluster Level Federation (CLF) formed from a group of SHGs in surrounding villages. While we are still at the very initial stages of the functioning of the agro-processing enterprise, there have already been some immensely valuable lessons learned during the journey thus far. This article highlights a few of these critical lessons. We also describe the processes we followed with the village women that both prompted these learnings and helped ensure that we are mindful of the lessons at every step!

The following lessons are not intended to be a prescriptive ‘How to?’ guide for anyone. These are being shared with the hope that they may provide a moment or two of reassurance, contemplation, and perhaps in the best case, illumination to anyone working with or planning to work with collectives-based enterprises, whether in rural India or beyond.

⚬ ⚬ ⚬

At the very onset of setting up the agro-processing enterprise, we were confronted with rather fundamental questions. What would the enterprise produce? Would our target customers (the SHG women and their households within a block) even buy the products manufactured at the processing centre? The insights we gained from just our initial interactions with the SHG/ CLF members and the MP SRLM team made it clear to us that there wasn’t a better way to answer this question than by listening to our customers and end users.

This realization was in many ways reassuring as it was consonant with what we call the ‘Imago Way.’ Central to the Imago Way is recognizing that the people closest to the experience, the struggle, or the opportunity (in this case, a chance to be a rural sales women entrepreneur–known as Unnat didi) are the ones with the knowledge. They know what they need. Our job is to invite a trust-based conversation, which begins with listening to the needs of the people closest to the problem.

How did we actually ‘listen’ to our customers? We followed a three-step process:

The initial and probably the most essential step was to have multiple participatory in-person interactions with the women, both at the cluster federation and the village level. The core idea was two-fold. First, we wanted to know who these women were and their realities, challenges, needs, and aspirations. Second, we wanted to gauge their initial interest and understand the target market for the proposed agro-processing enterprise model. It was essential to have these interactions with the women at different levels — with the CLF functionaries and with the SHG members at the village level, especially because women at different levels tend to have different realities and constraints. For instance, while the women in leadership positions, who were functionaries of the cluster-level federation, would usually express enthusiasm for the model, the SHG women at the village level would occasionally tend to have reservations about the model and whether it would even be possible for them to engage with it. We held a series of focus group discussions with the SHG women at the village level. Simultaneously, participatory discussions were held at the cluster level with CLF functionaries representing different villages. In addition, regular meetings and discussions were also held with the district-level and block-level teams from the government in the MP SRLM. All this helped in gaining and grasping both specific (village-level) and generic (broader cluster-level) insights and nuances about the realities of these SHG women, along with the complexities of the market that they would be entering.

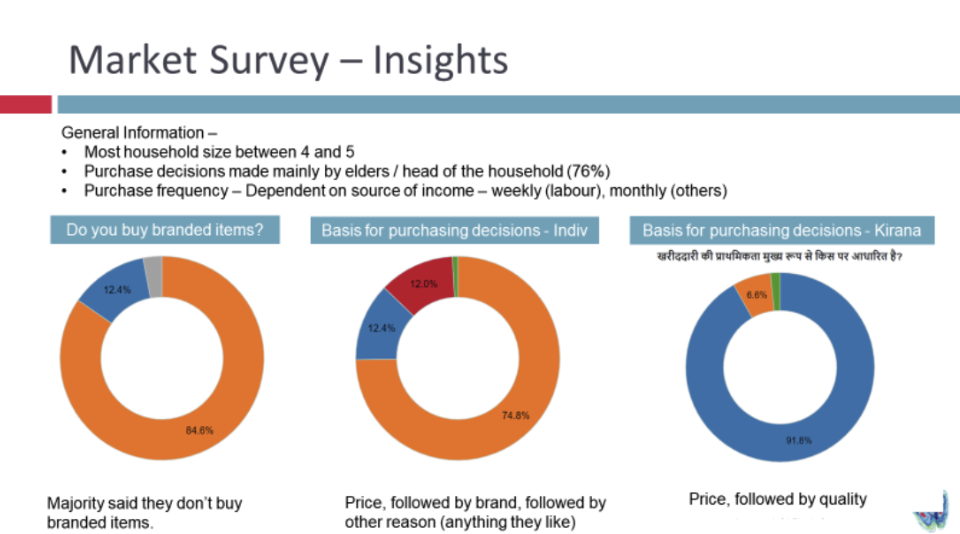

After some degree of familiarity with the local context through interactions and meetings with the community, our next step was to substantiate what we had understood about our customers. This was achieved by conducting a market survey within the block. SHG member households and local kirana (grocery shop) owners were surveyed to further understand the local market and customer behaviour. The extensive survey enabled us to expand the sample size of our market study to a significantly larger number of villages. The findings from the survey enriched us with crucial data that complemented and deepened the insights gained from qualitative listening, thus making the entire process even more robust. This helped us arrive at a tentative product basket for the processing centre, which was backed by both qualitative and quantitative evidence.

The third step in the process was to go back to the community to share what we had learned from the first two steps to ascertain whether our findings were truly accurate and pertinent. One of the main ways in which this was achieved was through a participatory workshop with the CLF members on the key findings of the market survey. The workshop’s objective was to validate the initial product basket and discuss the value proposition, potential brand name, and customer segments. The interest and involvement of the women during the session was enormously heartening. The workshop proved fruitful, and we managed to validate the product basket and arrive at the tentative brand name (which became the eventual brand name of the enterprise products in MP). We realized that besides gaining valuable feedback, this step was essential to building greater involvement and ownership of the primary stakeholders in the entire endeavour. Buy-in from the people closest to the problem and its solution is instrumental to the eventual success of the collective enterprise.

⚬ ⚬ ⚬

Now, while the process of listening to the community that we elucidated above may sound rather simple, at least on the surface, it can often be a classic case of easier said than done. It wasn’t until we had to visit the first village for our first round of interactions with the SHG members that we were left mulling over how best we could actually communicate with the women so that they trusted us and believed that what we were saying was truly genuine. It’s important to remember that these SHG members might be carrying the disappointment of unfulfilled promises by different actors and agencies in the past, which engenders well-founded scepticism within them towards any new initiative or actor. We realised, therefore, that it was critical to focus both on the message as well as on the messenger to establish trust with the community and to ensure their receptiveness during our interactions. How did we do this?

It began with identifying the right person(s)/ team to speak to in the community. The presence of community trainers who were familiar with the local context, and spoke the language that the community conversed in, was invaluable to building trust and confidence in the community. It was important for the SHG members to be able to relate to our mobilization team to ensure a participatory dialogue and avoid mere dissemination of information. A healthy sense of humour, candour, and an earnest sense of inquiry on the part of the community trainers goes a long way in engaging the participants and making them feel comfortable to share their stories. This helps in making the interaction distinctly memorable for the SHG members. One SHG member recalled fondly after an exchange — “Humein yaad hai bhaiya aap aaye the aur aapne humein masala udyog ke baare mein bataaya tha”, which loosely translates to “We remember that you came and that you had told us about the spice making enterprise.”

Identifying suitable trainers and the team to speak to the community is only half the job done. It was equally important to have detailed session plans with room for quick adaptation based on the insights gained in the field. The planning process also involved anticipating questions that the women may have and being prepared with a clear answer to those to avoid confusion and inconsistency. Thorough session plans were therefore co-created and were followed by dry runs by the trainers with the team to get feedback and suggestions that would help make the sessions interactive and fun while minimizing the scope for digressions and incoherence. These session plans were constantly revised based on the learnings from the field interactions.

(Sidenote: A community interaction tip that we found helpful was to focus initially on sharing and reinforcing the core idea/ macro details, allowing it sufficient time to sink, and then unpacking the micro-details by inviting questions rather than through one-way dissemination. Avoid information overload at all costs)

⚬ ⚬ ⚬

Working with people naturally entails a certain dynamism and unforeseen complexity, making it difficult always to have a water-tight plan. What we know is that one can only find out whether a plan works or not by agile testing and iteration. One of IMAGO’s core values is iterative and adaptive thinking and learning. From our experience, we have realized this is an inevitable to arrive at a tenable and productive plan.

The overall journey might look something like this; Prototype → Test → Iterate → Pilot → Protocolize.

One (among many) domains in which we followed the journey described above was the process of finalizing product branding and package size. We were naturally disposed to seek answers to critical questions regarding the optimal package size, brand design, and communication.

Taking one step at a time, before our on-ground immersion, the team worked with a marketing expert to design a few sample product packaging prototypes. Simultaneously, the tentative package sizes for each initial product were decided based on the market survey results. The prototype design was developed and shared with the CLF members during a participatory workshop. This workshop served as a hotbed of ideas, where the CLF members shared their inputs on the product design and the most commonly demanded package sizes. Ideas were shared on how the package design could embody and represent the product’s value proposition (for example, there was an agreement to include a transparent section in the design to symbolize the value of transparency that the CLF viewed as extremely important in building trust with the customers). At the same time, the feedback of the SRLM team was also incorporated, and the designs were quickly adapted after necessary iterations to arrive at the finalized packaging design and the most likely package size.

These were then piloted in the market with relatively small initial volumes. This was a necessary step to mitigate the risk related to customers’ purchasing preferences, particularly concerning the package sizes (for example, we tested whether the customers predominantly purchased 100 gm or 50 gm packets of turmeric powder at once). The pilot testing gave us critical data and market validation to protocolize the product-wise package sizes and design for a full-fledged market launch.

⚬ ⚬ ⚬

In hindsight, we realize this has been a journey from a state of ‘not knowing fully’ to the state of ‘knowing with reasonable conviction.’ While the path had been characterized by inherent uncertainty, working through it by quick testing and adapting has helped us to gradually overcome the challenges, one step at a time. Moreover, inviting and involving those closest to the experience to overcome their hurdles along the way has been vital and necessary. If not anything else, we’re absolutely certain to have more such wondrous lessons in the journey ahead!

This article is based on the work Imago Global Grassroots is currently engaged with Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) to scale RUDI via a government rural development program in the state of Madhya Pradesh in India.